Understanding The Bloch Sphere

21 Oct 2024

Introduction

In quantum computing, a qubit is a vector of the form

\[| \psi \rangle = a |0\rangle + b |1\rangle\]where $a,b\in\mathbb{C}$ are complex numbers satisfying

\[\langle \psi | \psi \rangle = |a|^2 + |b|^2 = 1\]In other words, the state space of a single qubit is the set of unit vectors in the two dimensional complex vector space $\mathbb{C}^2$ with basis vectors $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$.

Operations on a single qubit are linear transformations which preserve the norm and therefore correspond to $2\times 2$ unitary matrices $U \in U(2)$.

The vector space $\mathbb{C}^2$ is a four dimensional real vector space, and the constraint $|a|^2 + |b|^2 = 1$ means that the state space of a qubit can be identified with the three dimensional sphere in four dimensional space $S^3 \subset \mathbb{R}^4$. Concretely, if $a = x + yi$ and $b=z + wi$ then $|a|^2=x^2+y^2$ and $|b|^2 = z^2 + w^2$ and so the state space of a qubit consists of the points $(x,y,z,w)\in\mathbb{R}^4$ satisfying:

\[x^2 + y^2 + z^2 + w^2 = 1\]which is precisely the definition of a sphere in four dimensions with radius $1$.

It is difficult to visualize $S^3$ and even more difficult to imagine how it behaves under unitary transformations.

The Bloch Sphere is a projection of the state space onto the more familiar two dimensional sphere in three dimensional space $S^2 \subset \mathbb{R}^3$. Importantly, under this projection unitary transformations of the state space correspond to ordinary rotations of the sphere. Furthermore, there is an explicit formula that determines precisely which rotation corresponds to a given unitary matrix. This makes the Bloch Sphere an indispensible tool for analyzing single qubit operations.

The classic formula for the rotation of the Bloch Sphere associated to a unitary matrix $U$ is given in terms of matrix exponentials of Pauli Matrices.

The goal of this post is to present an alternative version of the formula that describes the rotation in terms of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of $U$. In addition to using only intrinsic properties of $U$, this version has a fairly intuitive proof.

We’ll conclude the post by using this alternative version to provide a succinct proof of the classic formula.

The Bloch Sphere

As stated in the introduction, a single qubit is a vector of the form

\[| \psi \rangle = a |0\rangle + b |1\rangle\]where $a,b\in\mathbb{C}$ are complex numbers satisfying

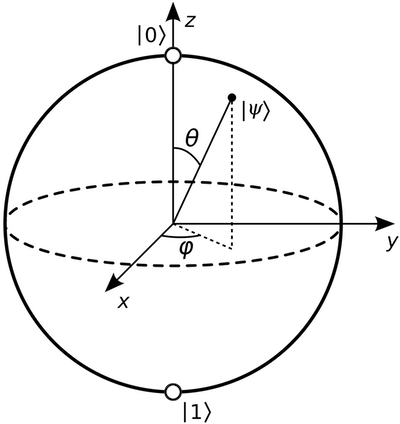

\[|a|^2 + |b|^2 = 1\]Due to this constraint, we can parameterize the qubit with three angles as:

\[| \psi \rangle = e^{i \varphi_0}\cos(\theta/2) |0\rangle + e^{i\varphi_1}\sin(\theta/2) |1\rangle\]We can factor out a global phase $e^{i \varphi_0}$ and, after defining $\varphi = \varphi_1 - \varphi_0$, rewrite this as:

\[| \psi \rangle = e^{i \varphi_0} \left(\cos(\theta/2) |0\rangle + e^{i\varphi}\sin(\theta/2) |1\rangle \right)\]Recall that in spherical coordinates the pair of angles $(\theta, \varphi)$ define a point on the unit sphere:

The Bloch sphere projection maps the qubit state $|\psi\rangle$ to the point on the sphere with spherical coordinates $(\theta,\varphi)$. In cartesian coordinates this point is equal to:

\[(\cos\varphi\sin\theta, \sin\varphi\sin\theta, \cos\theta) \in \mathbb{R}^3\]To facilitate notation, we will denote the Bloch projection by $\mathrm{Bloch}$:

\[\mathrm{Bloch} : \mathbb{C}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3\]Note that this projection ignores the global phase $e^{i \varphi_0}$. The physical motivation for this is that due to the properties of quantum measurement a global phase has no observable effect.

For example, consider the state:

\[|\psi\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(|0\rangle + |1\rangle\right)\]We can write this as

\[|\psi\rangle = \cos(\theta/2)|0\rangle + e^{i\cdot \varphi}\sin(\theta/2)|1\rangle\]for $\theta = \pi/2$ and $\varphi = 0$. Therefore, by the definition of the Bloch projection:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle) &= (\cos(0)\sin(\pi/2), \sin(0)\sin(\pi/2), \cos(\pi/2)) \\ &= (1, 0, 0) \end{align*}\]Unitary Transformations

Recall that a $2\times 2$ unitary matrix $U$ is a $2\times 2$ matrix with complex values satisfying

\[U U^* = I\]where $U^*$ denotes the complex conjugate of $U$. The set of unitary matrices together with matrix multiplication forms the Unitary Group denoted $\mathrm{U}(2)$.

We can represent a qubit state $|\psi\rangle = a|0\rangle + b|1\rangle$ as a length $2$ column vector in $\mathbb{C}^2$:

\[|\psi\rangle = \left[\begin{matrix}a\\b\end{matrix}\right]\]We can therefore transform a qubit state $|\psi\rangle$ by a unitary matrix $U$ via matrix multiplication:

\[U|\psi\rangle = U\left[\begin{matrix}a\\b\end{matrix}\right]\]For example, consider the state

\[|\psi\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(|0\rangle + |1\rangle\right)\]and the unitary matrix:

\[Z = \left[\begin{matrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{matrix}\right]\]Applying $Z$ to $|\psi\rangle$ gives us:

\[Z|\psi\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left(|0\rangle - |1\rangle\right)\]The Bloch Rotation Theorem

All operations (with the exception of measurement) that we can physically apply to a qubit can be represented by transformation by a unitary matrix $U$. It is therefore natural to wonder what multiplication by $U$ corresponds to on the Bloch sphere. Or, more precisely, what is the relationship between the points $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle)\in\mathbb{R}^3$ and $\mathrm{Bloch}(U|\psi\rangle)\in\mathbb{R}^3$?

Motivating Example

We’ll start by answering this question for the unitary matrix $Z$ from the previous example. If we apply $Z$ to a general qubit state:

\[|\psi\rangle = \cos(\theta/2)|0\rangle + e^{i\varphi}\sin(\theta/2)|1\rangle\]we get:

\[\begin{align*} Z|\psi\rangle &= \cos(\theta/2)|0\rangle - e^{i\varphi}\sin(\theta/2)|1\rangle \\ &= \cos(\theta/2)|0\rangle + e^{i(\varphi + \pi)}\sin(\theta/2)|1\rangle \end{align*}\]In terms of spherical coordinates, $Z$ transforms the coordinates $(\theta, \varphi)$ to $(\theta, \varphi + \pi)$. On the Bloch sphere, adding $\pi$ to the $\varphi$ coordinate corresponds to rotation by $\pi$ radians around the z-axis.

We can easily generalize this example to unitary matrices of the form

\[Z_\alpha = \left[\begin{matrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & e^{i\alpha} \end{matrix}\right]\]Clearly

\[Z_\alpha |\psi\rangle = \cos(\theta/2)|0\rangle + e^{i(\varphi + \alpha)}\sin(\theta/2)|1\rangle\]and so multiplication by $Z_\alpha$ corresponds to rotating the Bloch sphere by $\alpha$ radians around the z-axis.

Theorem Statement

We’ll now generalize the example in the previous section to an arbitrary unitary matrix $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$. In order to formalize the result, it is helpful to define the function

\[F : \mathrm{U}(2) \rightarrow \mathrm{Aut}(\mathbb{R}^3)\]which sends a unitary matrix $U$ to the corresponding automorphism of the Bloch sphere. In other words, $F$ is defined to satisfy

\[\mathrm{Bloch}(U|\psi\rangle) = F(U)\cdot\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle)\]for any qubit state $|\psi\rangle \in \mathbb{C}^2$ and unitary $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$.

We will also use the notation $\mathrm{Rot}_{\mathbf{n}}(\alpha)$ to denote rotation of $\mathbb{R}^3$ by $\alpha$ radians around the axis $\mathbf{n}\in\mathbb{R}^3$.

Using this notation, we can restate our above observations about $Z_\alpha$ more compactly as:

\[F(Z_\alpha) = \mathrm{Rot}_{\mathbf{z}}(\alpha)\]where $\mathbf{z} = (0, 0, 1)$ denotes the z-axis.

We can now state the general correspondence between unitary transformations of qubits and rotations of the Bloch Sphere.

Theorem (Bloch Rotation). Let $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ be a unitary matrix with eigenvalues $\lambda_1,\lambda_2\in\mathbb{C}$ and corresponding eigenvectors $|\psi_1\rangle,|\psi_2\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$. Then

\[F(U) = \mathrm{Rot}_{\mathbf{n}}(\alpha)\]Where $\mathbf{n} = \mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle)$ and $\alpha$ is the angle satisfying $\lambda_2/\lambda_1 = e^{i\alpha}$. In other words, transforming qubits by $U$ corresponds to rotating the Bloch Sphere by $\alpha$ radians around the axis $\mathbf{n}$.

To see how this works, let’s apply the theorem to the unitary matrix $Z_\alpha$ from the example above. The eigenvalues of $Z_\alpha$ are $\lambda_1 = 1$ and $\lambda_2=e^{i\alpha}$ with eigenvectors $|\psi_1\rangle=|0\rangle$ and $\psi_2\rangle=|1\rangle$.

According to the theorem, the axis of rotation is:

\[\mathbf{n} = \mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle) = \mathrm{Bloch}(|0\rangle) = (0, 0, 1)\]which is indeed equal to the z-axis $\mathbf{z}$. To find the angle of rotation, we can compute:

\[\lambda_2 / \lambda_1 = e^{i\alpha} / 1 = e^{i\alpha}\]which by the theorem implies that the angle of rotation is equal to $\alpha$ as we found above.

Note that it is not obvious from the definition of the Bloch projection that $F(U)$ is even a rotation at all. We can think of the Bloch Rotation theorem as consisting of two parts:

- A unitary transformation $U$ of qubit states corresponds to some rotation $F(U)$ of the Bloch sphere.

- A formula relating the angle and axis of the rotation $F(U)$ to the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of $U$.

In the next section we will prove the angle and axis formula under the assumption that $F(U)$ is indeed a rotation. In the following sections we’ll introduce an alternative formulation of the Bloch projection and use it to prove that $F(U)$ is always a rotation.

Proof: Part 1

In this section we will prove the Bloch Rotation theorem under the assumption that $F(U)$ is always a rotation of $\mathbb{R}^3$. The set of rotations of $\mathbb{R}^3$ forms a group called the Special Orthogonal Group denoted $\mathrm{SO}(3)$. So we can rephrase our assumption on $F$ as saying that $F$ is a function from the group of unitary matrices $\mathrm{U}(2)$ to the group of rotations $\mathrm{SO}(3)$:

\[F : \mathrm{U}(2) \rightarrow \mathrm{SO}(3)\]We saw in the previous section that the Bloch Rotation theorem holds for the unitary matrices

\[Z_\alpha = \left[\begin{matrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & e^{i\alpha} \end{matrix}\right]\]Our strategy to prove the general case is to show that an arbitrary unitary matrix $U$ can be transformed to $Z_\alpha$ using a change of coordinates. This will allow us to deduce the general case of the theorem from the special case of $Z_\alpha$.

We’ll start by proving some simple facts about the function $F$.

Lemma (Composition). Let $U$ and $V$ be unitary matrices. Then

\[F(UV) = F(U)F(V)\]

Proof. By the definition of $F$, for any state $|\psi\rangle$ we have:

\[\begin{align*} F(UV)\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle) &= \mathrm{Bloch}(UV|\psi\rangle) \\ &= F(U)\mathrm{Bloch}(V|\psi\rangle) \\ &= F(U)F(V)\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle) \end{align*}\]Since the Bloch projection is onto, this means that

\[F(UV)\mathbf{v} = F(U)F(V)\mathbf{v}\]for any vector $\mathbf{v}$ on the Bloch sphere which implies that $F(UV)=F(U)F(V)$.

q.e.d

Lemma (Inverse). Let $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ be a unitary matrix. Then

\[F(U^{-1}) = F(U)^{-1}\]

Proof. This follows directly from the composition lemma above and the fact that $F$ maps the identity in $\mathrm{U}(2)$ to the identity in $\mathrm{SO}(3)$.

q.e.d

Lemma (Scalar Multiplication). Let $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ be a unitary matrix and $\lambda\in\mathbb{C}$ be a complex number with norm $1$. Then

\[F(\lambda U) = F(U)\]

Proof. This follows immediately from the definition of $F$ and the fact that the Bloch projection is invariant under scalar multiplication by complex numbers with norm $1$.

q.e.d

Lemma (Z Axis). Let $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ be a unitary matrix and let $|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$ be the first column of $U$. Then

\[F(U)\mathbf{z} = \mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle)\]where $\mathbf{z}=(0,0,1)\in\mathbb{R}^3$ denotes the z-axis.

Proof. By the definition of $|\psi\rangle$,

\[U|0\rangle = |\psi\rangle\]Furthermore, direct calculation easily shows that

\[\mathrm{Bloch}(|0\rangle) = \mathbf{z}\]The claim follows from these two observations together with the definition of $F$:

\[\begin{align*} F(U)\mathbf{z} &= F(U)\mathrm{Bloch}(|0\rangle) \\ &= \mathrm{Bloch}(U|0\rangle) \\ &= \mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle) \end{align*}\]q.e.d

We are now ready to prove the Bloch Rotation theorem.

Let $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ be a unitary matrix. By the unitary property, it has two eigenvalues $\lambda_1,\lambda_2\in\mathbb{C}$ which both have an absolute value of $1$ (wikipedia). Let $|\psi_1\rangle,|\psi_2\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$ be the corresponding eigenvectors.

Let $V\in\mathbb{C}^{2\times 2}$ denote the matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors.

By the eigendecomposition theorem, we can factor $U$ as:

\[U = V \left[\begin{matrix} \lambda_1 & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_2 \end{matrix}\right] V^{-1}\]Dividing by $\lambda_1$ and setting $\alpha$ to satisfy $e^{i\alpha}=\lambda_2/\lambda_1$ we get:

\[\frac{1}{\lambda_1}U = V Z_\alpha V^{-1}\]By the scalar multiplication, composition and identity lemmas:

\[\begin{align*} F(U) &= F(\frac{1}{\lambda_1}U) \\ &= F(V Z_\alpha V^{-1}) \\ &= F(V) F(Z_\alpha) F(V)^{-1} \\ &= F(V)\mathrm{Rot}_\mathbf{z}(\alpha)F(V)^{-1} \end{align*}\]In summary:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:fu-decomp} F(U) = F(V)\mathrm{Rot}_\mathbf{z}(\alpha)F(V)^{-1} \end{equation}\]By the z-axis lemma and the definition of $V$, $F(V)$ transforms the z-axis in $\mathbb{R}^3$ to $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle)$. Combining this with equation \ref{eq:fu-decomp} we see that $F(U)$ first applies the rotation $F(V)^{-1}$ which rotates $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle)$ to the z-axis, then preforms a rotation of $\alpha$ radians around the z-axis and then applies $F(V)$ which rotates the z-axis back to $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle)$. This sequence of operations clearly fixes $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle)$. It is also easy to see that it rotates the plane orthogonal to $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle)$ by $\alpha$ radians. Together this proves the theorem.

Reflections

In this section we will start to develop an alternative formulation of the Bloch projection. In addition to being interesting in its own right, this new perspective will make it easy to prove that unitary transformations of qubits always correspond to rotations of the Bloch sphere which will complete our proof of the Bloch Rotation theorem.

Definition (Reflection). Let $|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$ be a qubit state. The reflection with axis $|\psi\rangle$, denoted $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)$, is defined to be the linear transformation of $\mathbb{C}^2$ that fixes $|\psi\rangle$ and scales the vector orthogonal to $|\psi\rangle$ by $-1$.

More concretely, if $|\psi^\perp\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$ denotes a vector orthogonal to $|\psi\rangle$ then $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)$ is defined to satisfy:

\[\begin{alignat*}{3} \mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle) &\cdot |\psi\rangle &&= &&|\psi\rangle \\ \mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle) &\cdot |\psi^\perp\rangle &&= -&&|\psi^\perp\rangle \end{alignat*}\]In terms of coordinates, if $|\psi\rangle = a|0\rangle + b|1\rangle$ then $|\psi^\perp\rangle = -b^*|0\rangle + a^*|1\rangle$ and so:

\[\begin{align}\label{eq:refl-coords} \mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle) &= \left[\begin{matrix} a & -b^* \\ b & a^* \end{matrix}\right] \left[\begin{matrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{matrix}\right] \left[\begin{matrix} a^* & b^* \\ -b & a \end{matrix}\right] \\ &= \left[\begin{matrix} aa^* - bb^* & 2ab^* \\ 2a^*b & -aa^* + bb^* \end{matrix}\right] \notag \end{align}\]Clearly the eigenvalues of $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)$ are $1$ and $-1$ which implies that $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)$ is Hermitian. Furthermore, since the trace of a matrix is equal to the sum of its eigenvalues, the trace of $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)$ is $0$. We’ll denote the vector space of $2\times 2$ Hermitian matrices with trace $0$ by $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ and define the reflection function:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{Ref} : \mathbb{C}^2 &\rightarrow \mathfrak{su}(2) \\ |\psi\rangle &\mapsto \mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle) \end{align*}\]Pauli Matrices

We’ll now find a basis for the vector space $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. Let $M \in \mathfrak{su}(2)$ be a matrix with coefficients:

\[M = \left[ \begin{matrix}a & b \\ c & d \end{matrix}\right]\]where $a,b,c,d \in \mathbb{C}$. The Hermitian condition means that $M=M^*$ and so

\[\left[ \begin{matrix}a & b \\ c & d \end{matrix}\right] = \left[ \begin{matrix}a^* & c^* \\ b^* & d^* \end{matrix}\right]\]This implies that $a$ and $d$ are real numbers and that $c = b^*$.

The trace $0$ condition implies that:

\[\mathrm{tr}(M) = a + d = 0\]and so $a = -d$. Setting $a=z\in\mathbb{R}$ and $c=x+yi\in\mathbb{C}$ we can write $M$ as:

\[M = \left[\begin{matrix}z & x-yi \\ x+yi & -z \end{matrix}\right] = x \left[\begin{matrix}0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{matrix}\right] + y \left[\begin{matrix}0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{matrix}\right] + z \left[\begin{matrix}1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{matrix}\right]\]for some real numbers $x,y,z\in\mathbb{R}$. The matrices

\[\begin{align*} X &= \left[ \begin{matrix}0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{matrix}\right] \\ Y &= \left[ \begin{matrix}0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{matrix}\right] \\ Z &= \left[ \begin{matrix}1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{matrix}\right] \end{align*}\]are called Pauli Matrices. It is easy to see that all three Pauli matrices are in $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. The above calculation shows that the Pauli matrices form a real basis for $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. In particular this implies that $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ is a three dimensional real vector space.

We’ll define the Pauli function

\[\mathrm{Pauli} : \mathfrak{su}(2) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3\]to be the function that sends a matrix $M\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$ to it’s coordinates with respect to the basis of Pauli matrices $X,Y,Z\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$.

The vector space $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ has an inner product defined by the Frobenious Product. Specifically, the inner product of $A,B\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$ is defined to be:

\[(A, B) := \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(AB^*)\]It is not hard to see via direct calculation that the Pauli matrices form an orthonormal basis for $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. For example:

\[XZ^* = \left[\begin{matrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{matrix}\right]\]which implies that $X$ and $Z$ are orthogonal:

\[(X, Z) = \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(XZ^*) = 0\]Another Path To Bloch

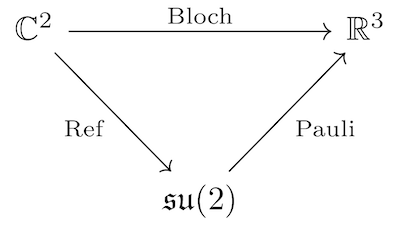

We can reformulate the Bloch projection in terms of the $\mathrm{Ref}$ and $\mathrm{Pauli}$ operators:

Claim (Bloch From Reflections). Let $|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$ be a qubit state. Then:

\[\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle) = \mathrm{Pauli}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle))\]

We can understand the claim in terms of the following diagram:

The diagram shows two ways to map a point in $\mathbb{C}^2$ to $\mathbb{R}^3$. We can either follow the top arrow or compose the two bottom ones. The claim states that both paths are equivalent.

The rest of this section will be dedicated to proving the claim.

First let’s obtain a more concrete version of the Pauli basis map $\mathrm{Pauli}$. Since the Pauli matrices $X,Y,Z\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$ form an orthonormal basis, the coordinates of a matrix $M\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$ in the Pauli basis are given by the inner products with $X$, $Y$ and $Z$:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:pauli-coords} \mathrm{Pauli}(M) = ((M, X), (M, Y), (M, Z)) \end{equation}\]Consider the qubit state

\[|\psi\rangle = a|0\rangle + b|1\rangle\]We’ll use equations \ref{eq:refl-coords} and \ref{eq:pauli-coords} to compute $\mathrm{Pauli}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle))$.

By equation \ref{eq:refl-coords} it’s easy to see that

\[\begin{alignat*}{3} (\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle), X) &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)X^*) &&= ab^* + a^*b \\ (\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle), Y) &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)Y^*) &&= i(ab^* - a^*b) \\ (\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle), Z) &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)Z^*) &&= aa^* - bb^* \end{alignat*}\]By equation \ref{eq:pauli-coords} this implies:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:pauli-refl-coords} \mathrm{Pauli}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)) = (ab^* + a^*b,\, i(ab^* - a^*b),\, aa^* - bb^*) \end{equation}\]If $|\psi\rangle$ has the form

\[|\psi\rangle = \cos(\theta/2)|0\rangle + e^{i\varphi}\sin(\theta/2)|1\rangle\]then plugging $a=\cos(\theta/2)$ and $b=e^{i\varphi}\sin(\theta/2)$ into equation \ref{eq:pauli-refl-coords}, together with standard trig identities and Euler’s formula gives us:

\[\mathrm{Pauli}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)) = (\cos\varphi\sin\theta, \sin\varphi\sin\theta, \cos\theta)\]which by definition is equal to $\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle)$. This concludes the proof of claim Bloch From Reflections.

Proof: Part 2

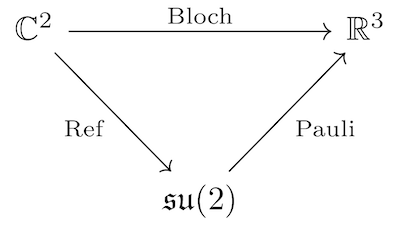

In this section we will prove that unitary transformations $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ on $\mathbb{C}^2$ correspond to rotations of the Bloch sphere in $\mathbb{R}^3$. This will complete the proof of the Bloch Rotation theorem.

To be precise, a rotation of $\mathbb{R}^3$ is defined as a linear transformation that preserves the inner product and orientation.

By claim Bloch From Reflections in the previous section, the Bloch projection can be decomposed into the composition of the reflection map $\mathrm{Ref}$ and the Pauli basis map:

Since $\mathrm{Pauli}$ is an isomorphism of inner product spaces, rotations of the inner product space $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ correspond under the $\mathrm{Pauli}$ map to rotations of $\mathbb{R}^3$. So we just need to show that unitary transformations of $\mathbb{C}^2$ correspond to rotations of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ under $\mathrm{Ref}$.

Let $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ be a unitary transformation. We will define $G(U)$ to be the corresponding transformation of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. More precisely, $G(U)$ is defined to be the unique transformation of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ satisfying:

\[\mathrm{Ref}(U|\psi\rangle) = G(U)\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)\]for all $|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$. Our goal in this section is to prove that for every unitary matrix $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$, $G(U)$ is a rotation of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$.

By definition, $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$ is a reflection along the vector $|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$. Similarly, $\mathrm{Ref}(U|\psi\rangle)\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$ is a reflection along the vector $U|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$. This means that we can obtain $\mathrm{Ref}(U|\psi\rangle)$ by applying a change of basis to $\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)$ via the unitary matrix $U$:

\[\mathrm{Ref}(U|\psi\rangle) = U\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi\rangle)U^*\]In particular, this implies that for all $M\in\mathfrak{su}(2)$:

\[G(U)\cdot M = UMU^*\]Clearly $G(U)$ is a linear transformation of $M$. We’ll now show that $G(U)$ preserves the inner product. Let $M$ and $N$ be elements of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. By the definition of the inner product, the trace cyclic property, and the fact that $U$ is unitary we have:

\[\begin{align*} (G(U)M, G(U)N) &= (UMU^*, UNU^*) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(UMU^*UN^*U^*) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(UMN^*U^*) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(MN^*U^*U) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{tr}(MN^*) \\ &= (M, N) \end{align*}\]This proves that $G(U)$ preserves the inner product. The last step in proving that $G(U)$ is a rotation is to show that it preserves orientation. To see why this is true, note that if $I\in\mathrm{U}(2)$ is the identity matrix then $G(I)$ is the identity on $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ and in particular preserves orientation. Since $\mathrm{U}(2)$ is connected and $G: \mathrm{U}(2) \rightarrow \mathrm{O}(3)$ is continuous, this implies that $G(U)$ preserves orientation for all $U\in\mathrm{U}(2)$.

The Pauli Vector Rotation Formula

The standard relationship between unitary transformations of qubits and rotations of the Bloch Sphere is stated in terms of Pauli Vectors. The Pauli Vector is defined to be the tuple of Pauli matrices:

\[\overrightarrow{\sigma} = \left(X,Y,Z\right)\]Analogously to the dot product, the product of a vector $\mathbf{v} = (x,y,z)\in\mathbb{R}^3$ and $\overrightarrow{\sigma}$ is defined to be:

\[\mathbf{v} \cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma} = xX + yY + zZ \in \mathfrak{su}(2)\]Since $\mathbf{v} \cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma}$ is a traceless Hermitian matrix, the matrix exponential $e^{i\mathbf{v} \cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma}}$ is unitary.

The connection to the Bloch Sphere comes from the following theorem:

Theorem (Pauli Vector Rotation Formula). Let $\theta\in\mathbb{R}$ be a real number and $\mathbf{n}\in\mathbb{R}^3$ be a unit vector. Let $U$ be the unitary matrix $U = e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}\mathbf{n}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma}} \in \mathrm{U}(2)$. Then transforming qubit states by $U$ corresponds to a rotation by $\theta$ radians around the axis $\mathbf{n}$ on the Bloch sphere. More precisely, for every qubit state $|\psi\rangle\in\mathbb{C}^2$:

\[\mathrm{Bloch}(U |\psi\rangle) = R_{\mathbf{n}}(\theta)(\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi\rangle))\]

We’ll prove this theorem using the Bloch Rotation theorem and Bloch From Reflections.

In order to apply the Bloch Rotation theorem to $U = e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}\mathbf{n}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma}}$ we need to find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of $U$. For this we’ll use the following lemma:

Lemma (Pauli Vector Norm). Let $\mathbf{v}\in\mathbb{R}^3$ be a vector. Then

\[\mathrm{det}(\mathbf{v}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma}) = -||\mathbf{v}||^2\]

Proof. We’ll denote the coordinates of $\mathbf{v}$ by $\mathbf{v}=(x,y,z)$. Then by the definition of $\overrightarrow{\sigma}$:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{v}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma} &= xX + yY + zZ \\ &= \left[\begin{matrix} z & x + yi \\ x - yi & -z \end{matrix}\right] \end{align*}\]And so

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{det}(\mathbf{v}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma}) &= -x^2 - y^2 - z^2 \\ &= -||\mathbf{v}||^2 \end{align*}\]q.e.d

To facilitate notation, we’ll define

\[M = \mathbf{n}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma}\]According to the lemma, if $||\mathbf{n}||=1$ then $\mathrm{det}(M)=-1$. Since $M=\mathbf{n}\cdot\overrightarrow{\sigma}$ is Hermitian with zero trace and determinant equal to $1$, this means that its eigenvalues $\lambda_1(M)$ and $\lambda_2(M)$ are real numbers satisfying:

\[\begin{alignat}{3} \lambda_1(M) + \lambda_2(M) &= \mathrm{tr}(M) &&= 0 \\ \lambda_1(M) \cdot \lambda_2(M) &= \mathrm{det}(M) &&= -1 \end{alignat}\]This means that one of the eiganvalues must be $1$ and the other is $-1$. We’ll set $\lambda_1(M)=1$ and $\lambda_2(M)=-1$. This means that we can diagonalize $M$ as:

\[M = V Z V^*\]where the columns of $V$ are the eigenvectors of $M$. By elementary properties of the matrix exponential, this implies that:

\[\begin{align*} U &= e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}M} = e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}VZV^*} = V e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}Z} V^* \\ &= V\left[\begin{matrix} e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}} & 0 \\ 0 & e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}} \end{matrix}\right]V^* \end{align*}\]This shows that the eigenvalues of $U$ are:

\[\begin{align*} \lambda_1(U) &= e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}} \\ \lambda_2(U) &= e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}} \end{align*}\]and that the eigenvectors of $U$ are equal to the eigenvectors of $M$.

We can now apply theorem Bloch Rotation to $U$. We just saw that the first eigenvector of $U$, $|\psi_1\rangle$ is equal to the first eigenvector of $M$. Since the eigenvalues of $M$ are $\lambda_1(M)=1$ and $\lambda_2(M)=-1$, $M$ is a reflection matrix and

\[\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi_1\rangle) = M\] \[\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle) = \mathrm{Pauli}(\mathrm{Ref}(|\psi_1\rangle)) = \mathrm{Pauli}(M)\]But since by definition $M = \mathbf{n} \cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma}$ we have:

\[\mathrm{Pauli}(M) = \mathbf{n}\]Together we’ve shown that

\[\mathrm{Bloch}(|\psi_1\rangle) = \mathbf{n}\]By the Bloch Rotation theorem this means that $U$ corresponds to a rotation of the Bloch Sphere around the axis $\mathbf{n}$.

Furthermore, since

\[\lambda_2(U) / \lambda_1(U) = e^{i\theta}\]the theorem implies that $U$ corresponds to rotation by $\theta$ radians around $\mathbf{n}$.

Comments

The comments are powered by the utterences Github app. If you do not want the app to post on your behalf, you can comment directly on this Github issue.